San Silvestro Oratory – a propaganda leaflet, or a treatise on political harmony?

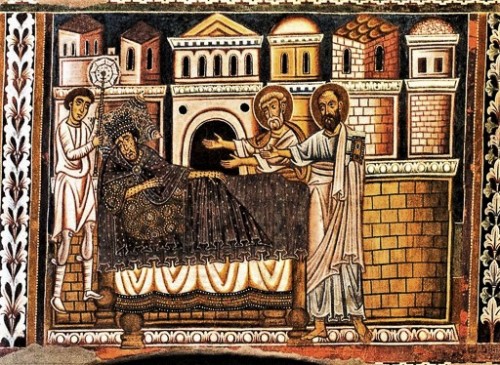

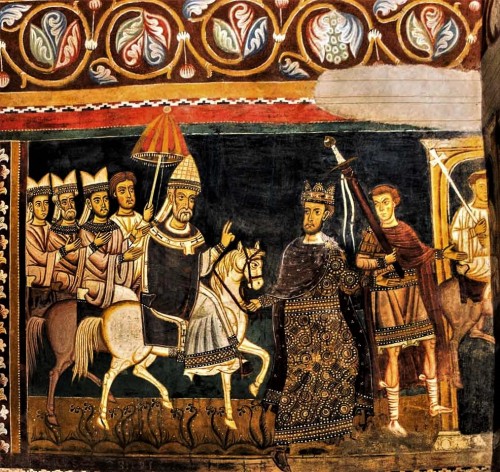

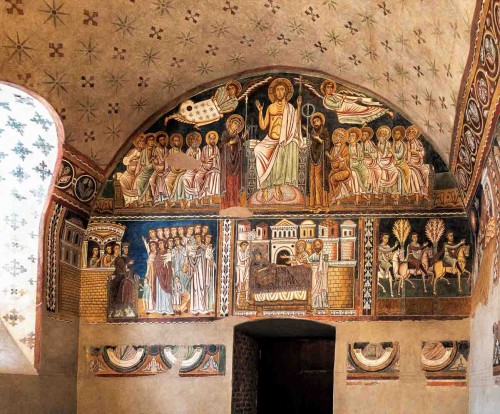

Above its portal there is a fresco depicting the four martyrs, understood as the four crowned stonemasons, the patrons of this church. In the lintel there is also an inscription commemorating them: Statuarium et lapicidarum corpus 1570, put up here in the year 1570, when the oratory came into the possession of the Guild of Stonemasons (working in marble). Prior to this taking place, this was a prayer chamber, which was richly decorated in 1246. And it is the frescoes created at the time which will be the topic of our interest. Upon entering we see a broad, rectangular room with a Cosmatesque floor, stone benches on the sides and a row of paintings on the walls. As if in an ancient comic book they depict the enthralling story of the first Christian emperor, Constantine the Great and the bishop of Rome, Silvester I. At the top like the sky, spreads the barrel vault, showing stylized crosses and stars. It is worth not only allowing ourselves to be charmed by the medieval painting beauty of these frescoes but also devoting a moment to decipher their ideological message, since it is more than interesting, but also, as we will see, mysterious. Above the enterance door to the oratory the first inaugural scene is located. It depicts the Christ Enthroned as the Judge, the Virgin Mary, John the Baptist, apostles, and the angels. All of these were called to testify about a matter very important to the Church, at least during the Middle Ages. What matter is this? Emperor Constantine, shown below, seated on a throne grants an audience to women begging for mercy for their children who were sentenced to death. His face, disfigured by pustules, turns towards them, while a gesture of his hand seems to calm them – as if to explain, that convinced by pagan priests he sought to find a cure for his leprosy by bathing in blood of innocent children, but ultimately he gave up on the idea. In the following scene, the emperor is already lying, felled by the illness, while two apostles, Peter and Paul, appear to him in a dream, stretching out their hands in a gesture of help and gratitude for saving the children. Apparently they are the ones who advised him to seek help from the bishop of Rome Silvester, who was in hiding from his persecutors at that time. As we can imagine, the emperor does not discount this advice, since in the following scene his envoys go the Monte Soratte, then begging Silvester to come to Rome. He apparently agrees, since in the next scene we see him as he preaches and teaches the kneeling emperor and converts him to Christianity. He also convinces him of the miraculous power of the apostles, showing him the image of Peter and Paul, of whom the emperor had dreamed and who will de facto free him from the disease. In the next scene Constantine already without the horrible pustules, small and nude as an infant is placed in a baptismal font, while Silvester places his hands on his head. The proportions of the bodies of the pope and the emperor speak for themselves. Next to a rachitic Constantine, Silvester seems to be a giant. Then, the emperor kneeling, this time in front of Silvester seated on a throne, hands him in a subordinate gesture, the Phrygian cap – the imperial conic cap, while also gifting him the imperial baldachin and a white steed. This transfer of headgear is especially important from the political standpoint. The pope puts on the Phrygian cap (the predecessor of the tiara), in this symbolic way putting on his head the earthly rule over Rome. The whole is completed by a crown, which is no longer on Constantine’s head, but remains within the city (behind city walls), held by one of his courtiers. On the following fresco the pope – already under the baldachin, with the Phrygian cap on his head and on a white steed, along with his church dignitaries is led into Rome by the emperor. We can clearly see that the pope holds all religious and earthly symbols of power, including the cross and sword held by the heralds. Constantine as the head groom once again appears with a crown on his head, which had in the meantime been symbolically placed on his head by the pope. We can only imagine, that in giving up his empire in thanks for the miraculous healing, the emperor leaves Rome and heads to the new, constructed on the Bosporus city – Constantinople, thus handing over the whole West to the pope.

The continuation of the paintings (on the opposite wall) is only indirectly connected with Emperor Constantine. They do however, show the supernatural powers of Pope Silvester. In the first scene we will see the bishop of Rome and the emperor’s mother Helena among Jewish rabbis. In the ongoing theological dispute the pope (a heavily damaged fresco), with the strength of his religious arguments defeats eleven adversaries. Only the twelfth rabbi remains, who was able to kill a bull calling the name of his god Yahweh. However, in restoring the animal’s life the pope managed to convince him of the superiority of Christianity. That is probably why Silvester is the patron of not only the new year but also of domesticated animals. Both the emperor’s mother as well as the rabbis are immediately baptized at the hands of Silvester, while Helena becomes a zealous follower of the new faith. This is proven by the next scene, in which the empress orders Golgotha in Jerusalem to be searched in order to find the True Cross. As we know, this search ended successfully. The last fresco, which we only know from a description, depicted the pope defeating a dragon that had terrorized Rome, which was a reason for the conversion into Christianity of a pagan priest astonished by this fact. This is how the story ends.

What we have seen is the firmly established in tradition legend based on two significant documents – the life of St. Silvester (Actus Silvestri) from the V century and the so-called Constitutum Constantini (Donation of Constantine). The frescoes on the left, these with the political message, were for the most part an illustration of this last document, which the Roman Catholic Church had recalled for centuries in its argument with the empire. Today we know that it was a spectacular forgery. It refers to a decree, in which the emperor allegedly bestowed upon the Church numerous estates and privileges, in this way giving it the right to rule over his empire.

The fact, that both these sources were used so many centuries after, had an important reason. The frescoes were a response, to the current, dramatic for the then pope, Innocent IV, events and clearly defined his position in the ongoing dispute with the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire – Frederick II. In 1244, meaning two years prior to the creation of these paintings, a bitter conflict broke out between these two dignitaries, and as a consequence the emperor was once again excommunicated by the pope. In the following year in fear of the imperial army of Frederick, who as a successor of the western Roman emperors exercised his right to rule over Rome, Innocent IV fled the city all the way to Lyon, where he hopelessly proclaimed the dethronement of the emperor. The frescoes created in the following year (1246) in the Oratory of St. Silvester, unambiguously emphasizing the primary role of the head of the Church, may only be viewed as an attempt to compensate for the humiliation which the pope had experienced. His stance in the paintings is clearly expressed. The pope rules not only over the city but over the whole empire and is not only the successor to St. Peter, but a ruler of the earthly state, anointed by Constantine. Perhaps the pope wanted to put the headstrong emperor, in his place. He chose this way, not with the aid of the sword, which he did not possess, but with art.

The frescoes were completed by Byzantine masters at the commission of Cardinal Stefano Conti. From the artistic standpoint they are not an outstanding work – the schematically treated architecture, lapidary landscape, unvaried gestures of the people, expressionless faces, however the decoration and along with it the naivety of these representations is from the modern point of view disarmingly charming. A sort of a novelty is the ambition to create, based on available documents, a historical narration which would correspond with temporality and contemporaneity, making this series an almost propaganda work of art.

The representation presented here is immensely popular. It convincingly depicts the pope, desiring to rule the world and force his authority onto the emperor and a defenseless emperor who sheepishly gives up Rome. Nevertheless, this is not the only interpretation. I would like to show another one as well, which while not as spectacular, seems more convincing to me. Its author is the German historian, Professor Matthias Thumser. According to him the founder of the fresco, who was de facto Stefano Conti – a cardinal and the papal vicar, but at the same time a member of a significant, oligarchic Roman family, a nephew of the great Pope Innocent III, in commissioning the creation of the paintings, desired to include within them a certain concept, concerning current times, designing a certain ideal vision, whose foundation was a balance between the authority of the pope, emperor and… Rome – understood as the center and head of the then western world. After the escape of Pope Innocent IV and the Roman Curia and the growing conflict with Emperor Frederick II, the political situation in the city was tense, while its future uncertain. The cardinal did however, see a certain solution. As in the past, Constantine felled by a disease, so in the present the blinded an stubborn Frederick should call the pope to Rome, recognize his spiritual superiority and allow the Roman Senate to place the imperial crown upon his head. This is the vision in a brief summary. The Romans themselves, understood as the Roman Senators, who, as previously the envoys of Constantine should convince the pope to return to the city, were to play an important role in this process. On the other hand, the loyal subjects of the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, should support him in cleansing himself from “leprosy” of pride, which is the desire to rule over Rome. He himself must lead the pope into Rome, give him authority over the city, while maintaining authority over the rest of the empire. The correctness of such a vision is proven by the previously described scene, in which Emperor Constantine leads Pope Silvester into the city. The imperial crown is at that time found in the hands of the dignitaries remaining inside the walls of Rome. They did not forget, that they are subjects of both the emperor as well as the pope – the ruler of the city. This message shows a desire to find the right balance in this difficult political struggle. It was expressed by a man who was devoted to the pope, however not dead set in his anger directed at Emperor Frederick, a proud Roman, convinced that Rome should not be an object of a barter, but a third political power, which in the struggle between the emperor and the pope may lead to peace and harmony.

Cardinal Conti as the pope’s vicar, desired to broadly disseminate the ideological or more appropriately propaganda program of his foundation. A forty-day indulgence for all who would visit the building decorated at his order on Good Friday and the following weeks, was to serve this goal. This is a testimony of not only a desire to show off the newly created work in Rome, but also to convince as many Romans as possible about his vision.

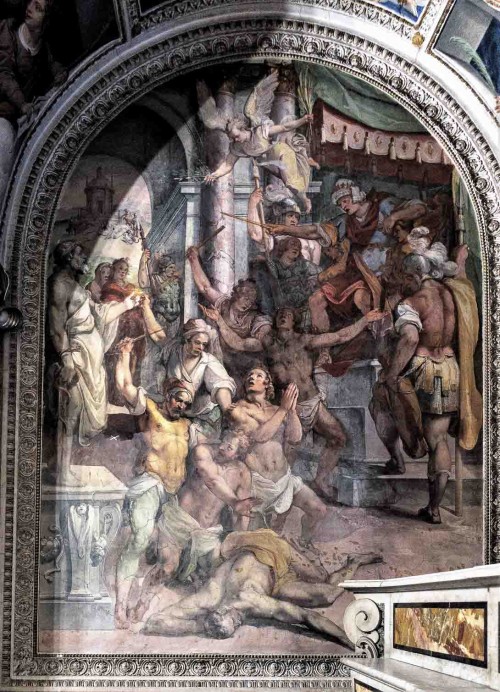

In the XVI century the oratory became the property of a guild of stonemasons and sculptors inhabiting the nearby area. Its responsibility was to keep it in the proper order, while its ambition was to enrich it, this time in the spirit of modernity. For this purpose painters were employed, who would immortalize the story of the martyr’s death of the church and guild patrons – the Four Crowned Martyrs, who as tradition would have it, at the order of Emperor Diocletian were executed for opposing the creation of the statue of a pagan god Asclepius which they were ordered to make. Before the new paintings found their way onto the walls, the southern wall of the oratory was pierced and an apse was created, in which an altar was placed. The Augustinian Sisters who had resided here since 1564 (in a cloister) and whose main task was caring for abandoned girls, were not forgotten either. In order to enable them to take part in the regularly celebrated masses, a kind of speakers were installed, which are still visible today among the painted medallions with stylized plant motifs, thanks to which the sisters could listen to the Word of the Lord. The frescoes of the choir and its vault were the work of Raffaellino da Reggio, while the ones on the walls, pilasters, as well as above the main enterance (from the outside), are a rather average work of the students of brothers Federico and Taddeo Zuccari. And here once again the clients did not forget the medieval series. On the walls of the triumphal arch we will notice its two main protagonists – Emperor Constantine and Pope Silvester I, this time in a Mannerist setting.

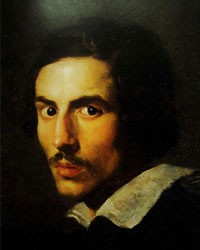

Still today, the members of the guild, which in the past boasted the most outstanding members, including Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Alessandro Algardi, meet here on the 8th of November, during the feast of the church patrons at a mass celebrated for the intention of stonemasons.

The oratory does not attract throngs of tourists, despite being a pearl of medieval art. As it turns out it is not the only one in this complex, which is still being discovered (see: Gothic Hall).

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108 or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !